Three years ago, Liza, Nisren, Hanan, and Jamila were enslaved by ISIS. At the time, Nisren was nine, the others in their twenties.

Like thousands of other Yazidi women, they watched as black-clad figures stormed their homes, shot their husbands and fathers, separated them from their children and took them as property.

Their village, Telezair, is not far from Mount Sinjar, a holy site where the Yazidi people were surrounded and killed en masse in what has since been recognised as a genocide.

As ISIS’s caliphate began to falter and crumble, all four escaped. They are alive, but in limbo, trying to figure out how to recover. One way to do this is by taking back control of their own stories – which, in part, they are doing by learning to paint.

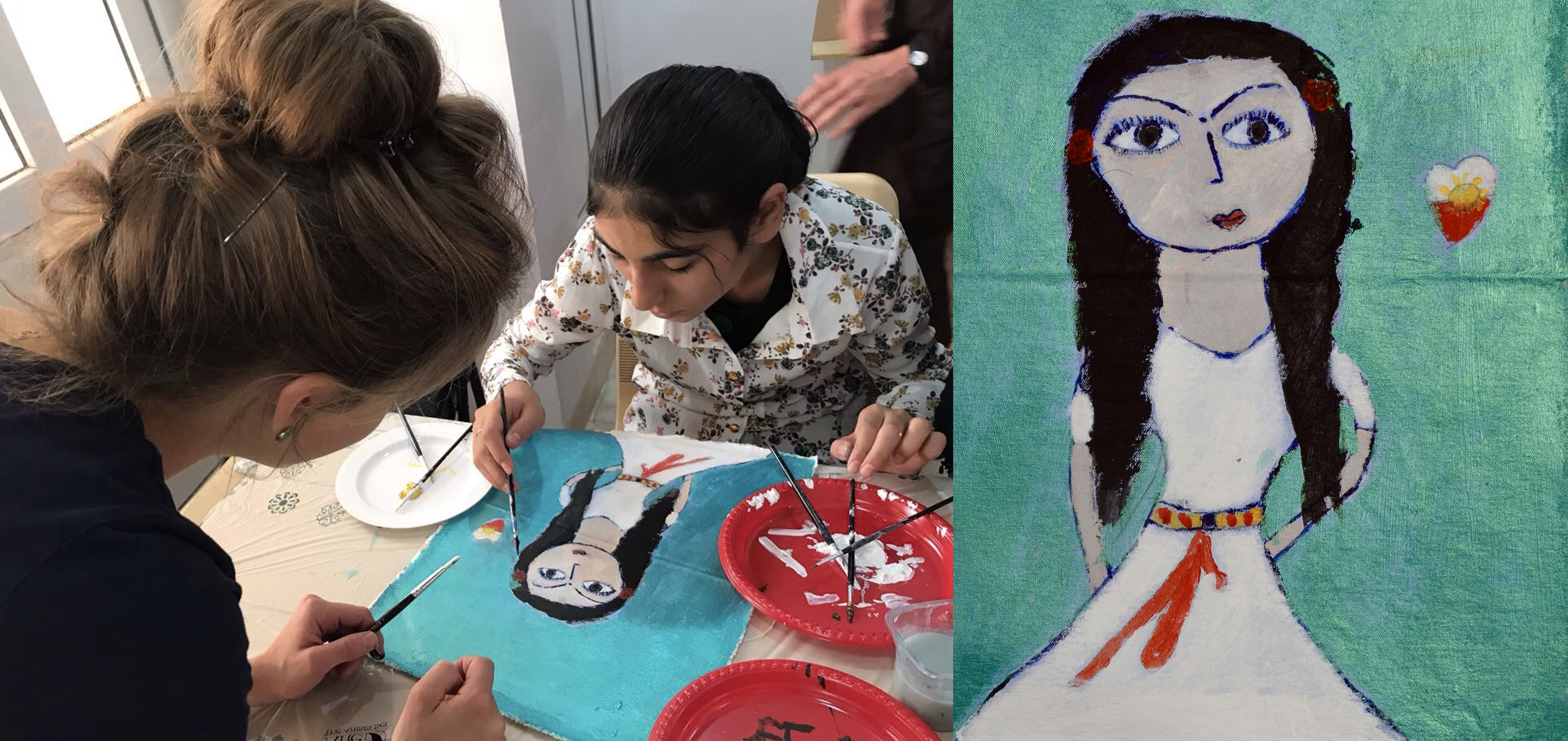

Hannah Rose Thomas, a British artist and linguist who works with the One Young World charity, is helping the women re-assert themselves. She ran a two-week painting workshop hosted by the Jinda Centre in Dohuk, Iraq, as part of international aid efforts.

Thomas shared the self-portraits with Business Insider and helped explain their significance. None of the women had ever painted before.

She said: "They were very keen that their paintings were shown to the rest of the world, I think because they want that restoration of dignity and humanity, particularly after the dehumanisation they faced by ISIS."

(Editor's note: Liza, Nisren, Hanan and Jamila are pseudonyms used at the request of the women)

Liza, 31

Liza is the eldest of the group. Thomas told Business Insider she is a "very motherly figure."

She has four children - two sons aged 11 and 8, a daughter aged 10, and another infant daughter. All but the youngest are still in ISIS captivity. Her husband was killed in the invasion. She was held in an underground prison for two years before escaping.

Like the rest of the women, Liza has painted herself in a variant of the white Yazidi ceremonial dress (she is wearing a version of it in the photograph above).

Around her neck, Liza has shown herself with a necklace in the shape of Kurdish letters, which spell "to God."

Describing the paintings as a group, Thomas said: "They convey such dignity. Some of them didn't want to paint tears and some did want to paint tears, and some of them brought in other parts of their culture, like the Yazidi flag.

"All of them wanted to paint themselves in the white, traditional dress. Which none of them had when they left because they were all in black and brown headscarves."

The Jinda Centre provided the white fabric Liza is wearing above.

Nisren, 13

Nisren is the youngest of the group, as was just nine years old when she was taken captive.

She managed to escape after seven months, but was separated from her mother, who she has not seen in years. She has been informally adopted by other Yazidi women in the groups. She has only fragmentary memories of her time with ISIS.

Thomas said: "This image feels very much separated from what she's experienced - she was painting an idealised image of herself as well, as one who's older. She also wanted flowers in her hair."

Older Yazidi women wear a headscarf, but for those Nisren's age and a few years older, it is normal to have uncovered hair.

Hanan, 25

Hanan is also a mother, but has not seen her six-year-old daughter since the two were separated from ISIS.

Unlike the other women, she showed ISIS in her portrait, depicting the moment she was separated from her child.

"I can never forget the day ISIS took her hands out of my hands," Thomas recalls her saying.

Hanan is the taller figure on the right, her daughter is on the left. The ISIS figure, bearded and in black, looms much larger.

Thomas said: "Hanan chose red for the background because it's symbolic of the blood of the martyrs - the many Yazidi men killed when the women and children were taken into captivity.

"There are tears coming from her eyes, and her child's. The figure of ISIS is much bigger and domineering. I think there is a strange kind of pathos in the image of ISIS with these staring eyes, which look very distressing.

"It's got this kind of deep anguish in those eyes, which is very disturbing. Most of the other women didn't want to do images which showed ISIS, which showed that side of it, death or the horrors that they'd witnessed."

Jamila, 27

Thomas said: "Jamila's in the white veil too, and she's got those tears because she wanted to paint an image of her sorrow.

"There's a silent sorrow there, with the mouth closed, and almost unspeakable grief - the way she's painted the eyes. They feel almost alive, they draw you right in and are filled with that grief. She wanted to paint the tears gold as well - it's showing that her tears haven't been forgotten as well, that they're precious and have value."

Referring to all of the pictures, Thomas concluded: "They are all standing so tall and straight, but silent as well, with great beauty and dignity. There's a sense that they haven't been broken by ISIS - they have deep sorrow but they're still standing and dignified and strong."